Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

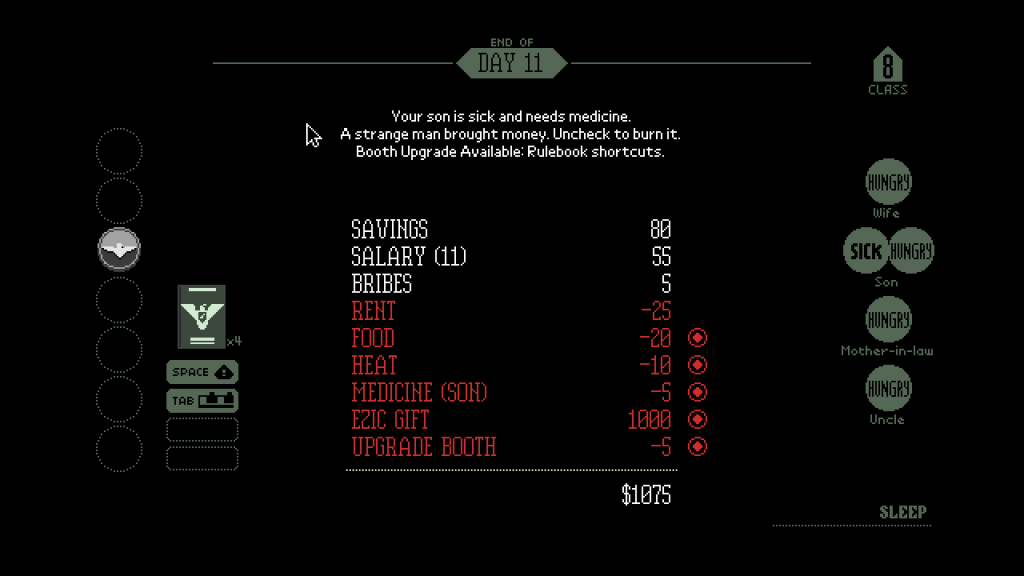

Papers, Please is a game in which the player takes over the role of a border agent in the fictional country of Arstotzka. The entire game takes place in a booth and the player encounters several migrants attempting to enter the country. The objective of the game is to review all of the documents presented by the migrants and decide to allow them entry, deny them, or detain them. The more migrants that are processed correctly either for entry or denial into the country, the more money the player earns, which is used for expenses at the end of the day towards rent, food, heat, and rent for the player’s in-game family.

One characteristic that Huizinga discusses in his article is the idea that play is “non-serious”(Huizinga 101). This is somewhat ironic considering that for a video game, the world that the player lives in throughout the game is fairly serious, as they hold the lives of many immigrants in their hand. But even if the world and aesthetic of the game is serious, the action of playing the game is not serious as it is a video game meaning our actions as a border agent do not have any effect in the real world, so we make our choices with less care, which is where Huizinga’s idea of “play is non-seriousness” comes in(Huizinga, 101). However, as the game goes on and the player begins to understand further the rules of the game and the world that the border agent lives in, the “play turns to seriousness” as the player becomes more and more immersed in the role of the agent and takes more care and caution when reviewing documents and choosing whether or not a person is eligible to enter the country (Huizinga, 103).

Another characteristic Huizinga discusses when describing play is the idea of freedom in play (Huizinga, 103). In the game, the player is allowed a few mistakes without repercussions before their mistakes cost them money for each mistake, meaning that the player has some freedom in which people they can allow into the country. This especially comes into play when some immigrants approach the agent with some sob stories about their families.

For one person in particular, Jorji, as shown in the figure above, approaches the booth with very entertaining dialogue that plays to the agent’s comedic side. I, for one, allowed him in instantly even though he didn’t have the proper papers because he was so funny and because I had the freedom to do so without repercussion. This choice made with the freedom allowed in the game even granted me with a few extra dollars.

Of course this also plays into the idea of Huizinga stating that when we play, we are out of the ordinary. When we have the freedom to do things like allow Jorji into the country, we “betray the seriousness” and do things that would be considered abnormal in the real world (Huizinga, 103).

Johan Huizinga. “Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomena.” Homo Ludens, 1938, pp. 95–120.

According to the article, “Game Analysis: Centipede”, during what people would refer to as a “Golden Age” of classic arcade games, many games lackluster in quality fell through the cracks of history while some like Pac-Man went on to become household names in the video game world. Pac-Man shares many of the characteristics that Rouse describes in his article on classic arcade games; It’s a single screen game that has no story, the player has an infinite amount of playtime so long as they do not run out of lives, and has a scoring/points system.

As far as gameplay goes, Pac-Man is easy enough for anyone to pick up. The player controls Pac-Man and moves him about in a maze picking up dots that grant him 10 points a pop. All the while, he is being chased by 4 different colored ghosts that move around him in random paths, and it’s the player’s job to avoid them or risk losing one of three lives if they touch the ghosts. If the player manages to consume a large, blinking coin then they receive a 50 point bonus and can deter the ghosts for a short period of time. If they consume the ghosts, the player receives up to 1600 points. The player receives one extra life for every 10,000 points earned.

Another trait that Rouse touches on in his analysis of Centipede that he considers to be significant to that game’s success that is shared in Pac-Man is the concept of “escalating tension”. Rouse describes Centipede as having “peaks and valleys”, but I would describe Pac-Man as an infinite climb to a peak that doesn’t exist. As you progress through each level, the ghosts start to move faster and faster and begin to chase after you with predictive movements rather than randomly encountering you. The larger coins that allow players to consume the ghosts also lose their effectiveness in later levels, making the time that Pac-Man is able to consume them much shorter every time. However, to provide some sort of a cushion to the raising difficulty, there are various fruits available that grant larger point values, thus making the climb to an extra life a little more feasible. The later stages in the game is what I think hooks people. The rising difficulty ceiling forces players to challenge themselves, and convinces them that they need to keep playing if they want to get better, which in turn falls into what Rouse discusses when he mentions the need for these games to be profitable for the developers.

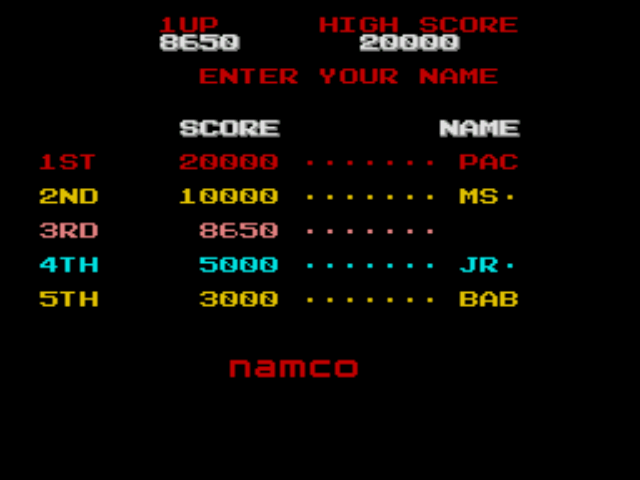

Pac-Man has all of the hallmark traits of what Rouse describes as a truly “classic arcade” game. It is a perfect blend of simplicity that draws in any and all who desire to drop in a few quarters to play, and slowly but surely cranks up the difficulty. At the end, the “bragging rights” that Rouse mentions come into play in a big way as the game can show which players have the highest scores, which results in players wanting to beat whoever is above them.

It isn’t the most technologically advanced game, but it is and will always remain a classic in the hearts of gamers all around.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.